I wrote my first big story in fourth grade. I called it, Adventures on the Amazon. It’s now lost to history, but I remember organizing it into chapters.

Chapters were a big deal. I’d never written anything so long that it could be divided into paragraphs, much less chapters.

Each chapter was a little–kid-against-nature story. I battled hungry piranhas, pygmies with blow-darts, hippopotami, elephants, boa constrictors, fire ants, and so on.

It was a long story. My teacher awarded an A and invited me to read before the class. When I finished, my classmates applauded, so I decided to keep writing.

My next big project was in seventh grade. In long-hand, I wrote a four-thousand word story about torture called, I am not a Coward. In it I tortured my brother to death to prove to the townspeople I wasn’t a coward. When I carried my dead brother into the heart of town to show the people what I had done, they weren’t proud of me like I hoped. Instead, they turned on me in horror and stoned me to death, while I screamed I am not a coward, I am not a coward!

I can’t tell you why I wrote Coward. I lack the courage to tell anyone why. I suppose I’ll be taking my reason to the grave. I really am a coward.

Before I showed the story to anyone, I taught myself to type. I thought, a story this good has to be typed. It deserves the simple dignity of a formal type-set. So I spent the summer with a book I talked mom into buying called Teach Yourself to Type in Ten Weeks. I used it over the summer, between seventh and eighth grade, to give me the skills to type out my masterpiece.

It felt like I’d conquered the world, once I finished the typing. I had taught myself to type and written an incredible story, all without the aid of a teacher. It was important to me and a source of pride.

I decided to read, I am not a Coward, to my family. Dad gathered everyone into our small living room for the dramatic presentation. Excitement lay on every face. Billy Lee had written a story. He could write. Everyone beamed with anticipation. They were proud of me, it was easy to see. I cleared my throat and began:

They say I am a coward. They say I watched my brother burn to death without lifting a finger to save him.

Dad lifted his hand. Hold on there, Billy Lee, he said, white-faced. He ordered everyone to leave the room. I think it would be better if you read this story to me, first. After the last family member had scampered away, he motioned for me to start.

So I read the story through to the end, while he sat across from me, silent. It took about a half-hour. When I finished, he paused to gather his thoughts. Billy Lee, he finally said. That’s the finest piece of mis-directed talent I’ve ever heard. Please don’t read it to anyone else.

It’s just not possible to suppress a story that rises to the level of I am Not a Coward. Over the next few months I gave private readings to friends, when Dad wasn’t home. After a while I had read it to everyone I knew, so I hid my story to protect it.

How I was able to preserve and protect my story over the years is nothing short of miraculous. I lived in a Navy family, after all. We moved every two years or so. My dad liked to say that every move is like a house fire. Things burn-up. Things get misplaced and go missing. Yet almost sixty years later, I am not a Coward survives.

During high school I wrote a number of stories that teachers asked me to read before students. I won’t bore you. But one story slowed my momentum. In ninth grade a closeted-gay teacher led my creative writing class. I submitted a story about a Navy medical corps-man who hid his gay identity.

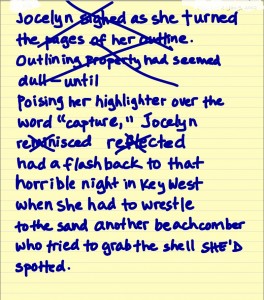

The teacher seemed to dislike it. He gave it an A-minus. He told me I was a lazy writer, because I used too many adjectives. More powerful verbs and adverbs were the answer. Even today, as I write, his comments roll around inside my head. I still love adjectives. Some of them are just perfect, as far as I’m concerned.

In college, money was scarce. To earn money for beer or whatever, I wrote term papers for people. I wrote under-graduate papers on economics, history and english, mostly. I charged by the grade, so getting an A was important.

I wrote only one paper at the graduate level — a microeconomics study on a currently successful Japanese company selected by the student. I invented the company I selected. Everything about it was imagined — even its name was fiction. My customer’s grade? A. I knew nothing about economics or Japan. Yes, I had taken a freshman econ class, and yes, I had lived in Japan — when I was in kindergarten. Apparently, it was enough. My writing career was on fire.

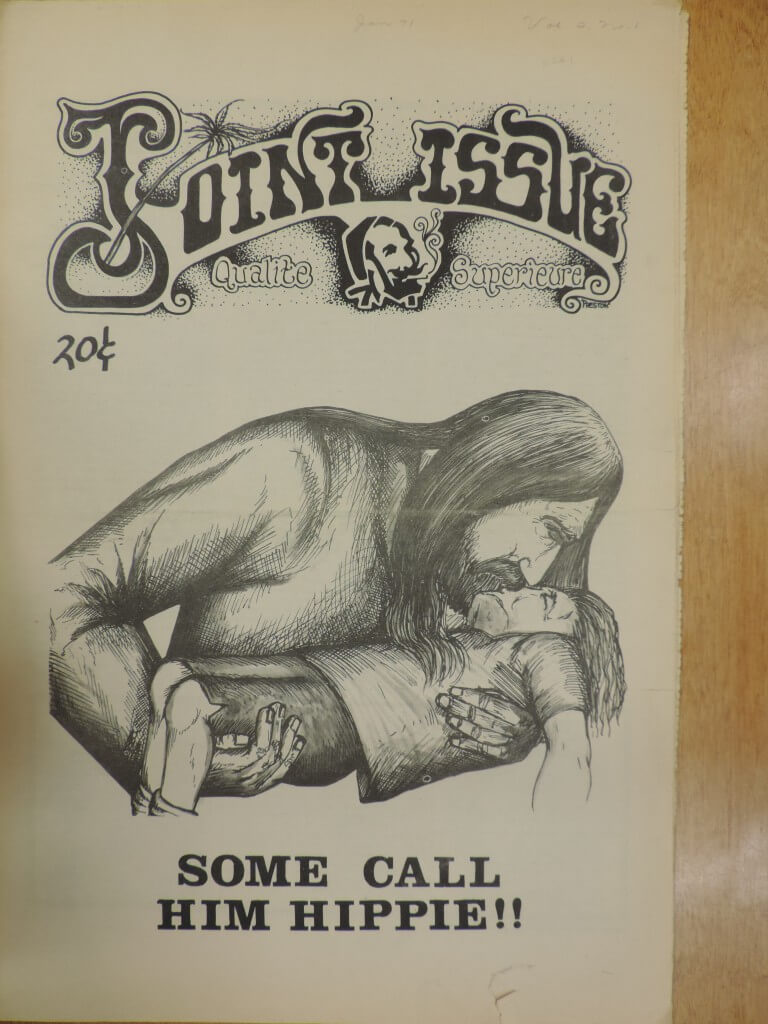

Eventually I dropped out of college to join the anti-Vietnam-war movement. I worked on staff for a community anti-war underground newspaper. All articles were critiqued and followed a commonly agreed to set of values. I found I wasn’t free to write, because every piece had to get by staff who had their own ideas about what was appropriate for our fifteen-thousand readers.

Though I continued to write and publish, my articles never seemed to rise to the level of good. People read our paper. It was highly circulated for an underground. We did some things right, I suppose. But I can understand why staff-writers on newspapers and magazines today feel the same pressures I did to conform to the values of the people who decide if they will be published. No one is the Lone Ranger, especially where writing is a business driven by profits or, in our case, ideology.

I stopped writing during my career as a mechanical engineer and machine designer. But eventually, after four decades, I retired. I thought, maybe it would be fun to start writing again. My writing skills lay rusty, in ruins, really. Why not start a blog, I thought to myself, and write about what I’ve learned and know? Maybe I’ll write about things I don’t know, too. Maybe I’ll pontificate, if I feel like it. Who can stop me? I had this crazy idea I could write anything. If I sounded like a communist at times, so what? Who was going to fire me? I was retired. I was free, and I was going to write like it.

Some in my family were blustering and pontificating on Facebook, crowding out the pictures and videos of grandchildren. I thought, why not give people another place to pontificate? It might go a long way to help free up the space we depended on to provide news about our little people. I figured readership would be tiny. I would fly under the radar of hostile readers, if hostile people actually lived in cyber-land as was sometimes rumored.

The first unusual thing happened right away, after I published a short story about a gay physician’s assistant. Almost immediately a swarm of Asian bots from the women’s apparel industry attacked my site. Anonymous comments piled up fast. More bots landed from USA cosmetic and high-fashion sites. What was going on?

I reread my article. It was supposed to be neutral. It was supposed to describe the gulf between gays and Christians on the subject of marriage and hint at some possible common ground of interest and attitude. But the writing was poor. The article tilted strongly toward a Christian point of view. It lacked ambiguity and neutrality — important components in articles designed to make people think.

I rewrote the story. And I put restrictions on comments. From now on each comment would be reviewed before posting to make sure it was from a living person. Overnight, the attacks stopped. I had peace on my blog-site. My family could continue to indulge me, reading my pontifications to help me feel loved and listened to in my old age, I supposed.

I puttered along writing articles about everything and anything that popped into my head. After writing about twenty-five posts, I decided to do something different: something bold; something experimental. I would self-disclose my sexuality and challenge readers to drop their prejudices against gays. I wrote the article, tidied it up and pushed the publish button. All hell broke loose.*

WordPress, keeper of my blog-site, alerted me to unusually high view volume. I looked up my stats. Site views were running ten times normal and piling up fast. At first I thought, wow, people like my blog.

The truth was, some thought I was advocating for homosexuality. They believed my views were against the Bible, inspired by satan, and possibly embarrassing to my family. People swarmed my site trying to understand the article and how to respond to it. Some decided that, unless I took down my post, they would turn me in to church-elders, a necessary prelude to (if I didn’t cooperate) church-discipline, even to possible excommunication.

But by then church leaders were already rummaging through my articles. Some articles, they found wanting. Their attitude was, since I belonged to their church, because I was a baptized covenant member, I certainly was not free to say anything I wanted. Everything I wrote had to be consistent with scripture and what they thought it said. To show they meant business, they disbanded my Bible-study group and removed me from leadership.

Church leaders wrote me a letter which included a bullet-list of concerns. They announced my punishments. They presented another list; this time, demands. They expected me to comply, and comply is what I did.

I took down the offending article. My seventy-one year old wife was recovering from open-heart surgery. All her friends are in our church. The last thing we needed was to undergo an excommunication. Like Galileo, who blasphemed Jesus and the Catholic church by making the absurd claim that Earth was not the center of the universe, it was recant or be tortured — because having my blog ripped out from under me feels like torture. I didn’t see it coming.

Church leaders say they love me and want what’s best for my soul. I believe them. It’s what I want too. And truth is, my article was edgy. It pushed a lot of boundaries, even mine. I didn’t like some parts of the article either, it turned out. No one wants to go to Hell. No one wants to forfeit the love of Jesus. No one wants to lose friends they’ve had for decades over an article or two in a blog. I get that. I feel it, too.

Decades spent in prayer, renouncing sin, loving the unlovable, giving aid to the wretched — the things we do as part of submitting to the will of Jesus — these things are supposed to humble us. But I want to write, unafraid, if possible. I can’t know, always, if something I write is going to offend someone well versed in the theology of our church.

In life, we all want to get it right. I don’t want to upset anyone. But no one gets it right one-hundred percent of the time; not even close. Even with a team of the best advisors available, no one gets it right all the time. Entire nations of praying people march off the cliffs of history, sometimes.

I have this idea that in America we have freedom of speech only if no one is listening to us. As soon as a handful of people start reading our stuff, even if it’s just family and a few Facebook friends, some people make it their business to bend us to their ideas of what is appropriate.

Freedom of speech means little more than bragging-rights to the people who run our country and manage our institutions, it seems to me. They brag to the world about how free we are; how easy it is to speak our minds. But try to publish. See what happens.

Start a blog and try to find your voice. Speak freely, tell it like it is, as you, your unique self, sees it — uncensored and unafraid — if only with your family and close friends. If you think America is the land of the free, you might be in for a sad surprise.

Billy Lee

* Note: we’ve included a link to the re-written, re-titled and sanitized version of the original article, Christian Love and Gay Pride. The rewritten version, which better articulates the views of Billy Lee, is called, Gay Love and Christian Pride. The Editorial Board