People hate me. People have hated on me my whole life, but never more than now, it seems, in my old age, when I need their love so bad. If they only knew how their hatred weakens me and any hope I have for happiness. Maybe they’d relent and welcome me into their friendly world.

But I don’t think so. If they knew how much I hurt, they’d hate me more, shun and isolate me even further, just to watch me suffer.

As Torrold DeShaun “Rod” Smart, the would-be NFL star, once said: I feel as if everyone hates me, from my mom to my dad and even my brothers and sisters; everyone ”Hates Me.”

The first time I learned people hate me was at the Army boot-camp for officer-candidates at Fort Benning, Georgia during the summer of 1968. I went there to train after becoming an officer candidate to avoid the military draft during the Vietnam War.

It was a period in our history when the government conscripted hundreds of thousands of young men to fight in Vietnam. Exemptions from the draft (called deferments) had been given to college students for years, but no longer.

Students across the country began competing to get into Army ROTC training programs, because they were the only sure way to stay in school and avoid military service, at least temporarily. At my school, I was one of only eighteen students (out of a pool of several thousand applicants) who qualified for officer training.

I felt lucky, because now I could finish my education. Maybe, by the time of my graduation, the war would be over.

At officer boot-camp that summer, in the humid choking heat of Georgia, the training began. The recruits were, like me, the cream of the crop, the best of the best, from some of the finest colleges and universities in the USA and around the world. I’ve not been with smarter, worthier people than those who shared my summer of ’68 at Fort Benning.

We found ourselves trapped in the grasp of some of the most ignorant, mean-spirited drill sergeants I’ve ever encountered. Their mission was to squeeze each recruit through a juice-grinder to see what we were made of and to prove to the military how strong (or how weak) were our minds and bodies.

They cursed us, abused us, deprived us of sleep and dignity, and told us we were over-privileged swamp scum, not worthy of the army. They convinced me they meant every word.

In chow-lines, gnarly swamp-people with missing teeth menaced and taunted us by swearing, shoving and pointing fingers. One officer forced recruits to eat their own cigarettes.

During a month-and-a-half of hell, I watched people go beserk on the firing range, collapse with seizures due to excessive heat and lack of water, quit the program, and go mad.

All I thought about during those forty-two days in Hell was this: it can’t last forever. I can survive, I can hold on, I can sleep again with my sweet girl-friend, Mary-Ann, who loves me. All this pain, this agony, will fade to an unpleasant memory, nothing more, in good time.

But, of course, I was naïve. Every dinner has its dessert, its crème-de-la-crème, its grand-finale, its coup-de-grace. Boot-camp was no different.

Two days before the end of training, the Army announced that each cadet in every forty-three-man platoon would participate in mandatory peer-reviews of their fellows. Drill Instructors — armed with notepads and pencils — ordered every officer-candidate to rank every other officer-candidate, from top to bottom.

Worst of all, the DIs forced each cadet to write an explanatory paragraph about each soldier they placed in the bottom-five. I think I remember trying to say something nice about each one of the five I chose.

As it happened, the evening after the peer-review, one of the cadets broke into the administration building and stole the reviews. Word got around, and soon a few dozen cadets, including me, gathered outside the barracks to rummage through them, their summaries and explanatory comments.

I discovered that my fellow cadets ranked me third from the bottom. I couldn’t grasp it, it seemed so unreal, so I read the comments. Apparently, I lost equipment, stole things, went AWOL, and was generally unprepared and unkempt.

I lacked the intelligence required to lead, lacked problem solving skills, etc. etc., on and on. I kept checking the name to see if it was mine. Nothing written about me was true.

It occurred to me that all of it — all the negativity and cruelty; every last hateful condemning word — was going to be part of my permanent record, my profile, which would follow me forever in the army and beyond.

Why, I asked myself over and over, would people who I thought were my friends write nasty, untrue, career-ending things about me? I couldn’t work out the answer.

Officer training camp broke me. I spent the next two days drunk, sobbing silently inside myself. On the last day, while the other cadets scurried to leave, I writhed on the floor by my bunk, unable to pack my things or police my area. Psychological trauma and grief immobilized me. The pain of being hated ruined me. I never recovered.

Billy Lee

Editor’s note: This article has been a fictionalized compilation of actual events, which occurred during two training camps — the first at Fort Benning, Georgia; the second at Fort Riley, Kansas the following summer. The stolen peer-reviews incident occurred at Fort Riley during the summer of 1969.

Incidents in the two camps have been conflated by Billy Lee to make a more comprehensible read. The incidents are true. The order is true. But events happened over consecutive camps — basic training and advanced infantry training the following summer.

P.S. Since writing this article, some people have asked me if, over the years, I might not have garnered some insight into why my ROTC compatriots at Fort Riley rejected me. (At Fort Benning, peer reviews weren’t conducted.)

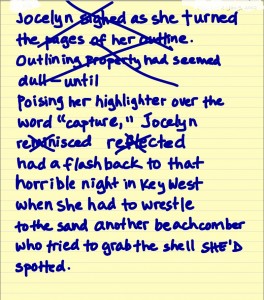

The answer is yes, but these insights weren’t included in the article, so that readers (who might not know me well) could experience the wonder I felt. In truth, (allow me first to lie; the truth is too painful) I was well-connected and proud. People hate arrogance, and that is what I was. I received special treatment from higher-ups. That, and my attitude, didn’t go over well. (Will you permit me to do some preliminary blame-shifting?)

General Boatwright, the base commander at Fort Riley — who knew my dad — gave me an escort on his private plane to camp. I boasted about it. Later, he flew to our bivouac-site with a half dozen helicopters and called me out of formation (as I remember it, with a bull-horn) to interview me in front of everyone about camp conditions. I remember he asked about the food and how we were treated. I told him everything was great.

The General invited me to what I think I remember was his daughter’s birthday celebration, which meant I had to abandon my buddies to harsh camp conditions, while I partied.

Later, I wrote a thank-you letter to the General, which a drill instructor somehow managed to intercept. He read it aloud at morning reveille to my gathered platoon. In front of everyone, the outraged DI tore up my letter, while he explained so that even a child could understand: cadets don’t write letters to Generals.

None of these incidents helped me get a good peer review. (Listen to me shuck and jive over these irrelevant incidents. Patience, please. I’m working my way to truth, but it’s hard)

The most damaging things that happened were self-inflicted. I remember bragging about myself to others. (Here comes partial self-serving approximations of truth.) I told wildly exaggerated stories to hide the truth about myself from others. The truth was, I hated the choices I made. I bragged about myself, but I bragged about things no one should be proud of — like the details of my sex-life.

I self-destructed. Yes, I hated the Army. Yes, I hated war. Yes, I trapped myself in a place I didn’t want to be. I made it embarrassingly obvious to everyone. I hated myself.

I couldn’t believe the terrible decisions I’d made. I couldn’t believe what a coward I was; how I caved to the powerful idiots who took us into the genocidal killing-field that was Vietnam for no other purpose than to test our newest equipment and evaluate our effectiveness to wage war. (More tangential bullshit is on its way.)

I found myself in a space I didn’t want to be, doing things I didn’t believe, for reasons that made no sense. I was scared to pay the price that came with resisting the evil I saw so clearly once I immersed myself in it. I had abandoned my point of view, my sense of what was right and wrong; my identity; my sense of self; my integrity. (If only any of this were true!)

Why, under the stress of basic training, did I turn on myself? Why did I manipulate others to turn on me? Why did I work so hard to bring the Universe of judgment and condemnation down on my pathetic-loathing-self? I would have to wait until many years later in therapy to learn the answers. (And I can never share them. Why don’t you understand? It’s killing me. I’m so afraid.)

I became obnoxious and inauthentic. It must have been obvious to everyone but me. It’s a wonder one of the cadets didn’t shoot me. They turned on me, because to them I was a sick puppy and a phony to boot. I wouldn’t own up. I was a coward. I refused to embrace the truth about myself.

Today, it’s clear to me that way back then in the fevered heat of officer training camp my peers would have ranked me at the very bottom of the pile had it not been for a couple of loving, perceptive souls who shared my pain and placed me, mercifully, carefully, near the very top.

Their act of kindness meant that when the scores were averaged, two other cadets would suffer the excruciating shame of being hated even more than me. Imagine. Hated more than me! HaHa! HaHaHa! Burp.

Billy Lee