ESSAY CONTAINS ADULT CONTENT

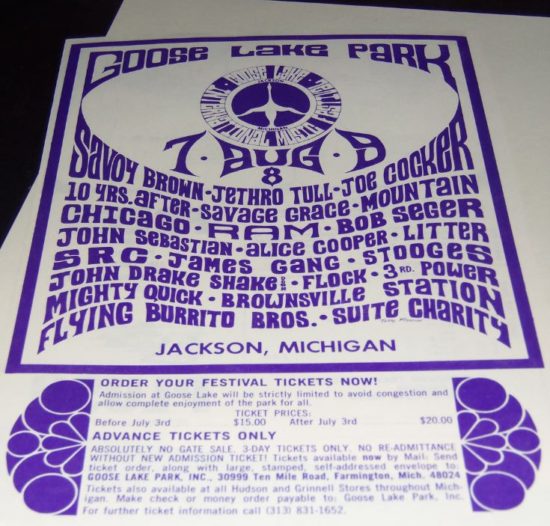

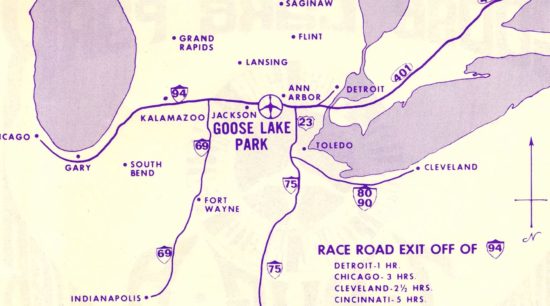

The 300,000 people who attended the Goose Lake International Music Festival on the east side of Leoni Township in Michigan during August 7-9, 1970 were mostly middle-class college dropouts like myself.

I dropped out in June—two courses short of a degree—to evade being shipped to southeast Asia to kill “gooks”. The university ROTC program trained future officers to lead Army combat platoons—destination Vietnam. After hearing horror stories from returning GIs during advanced infantry training at Fort Riley, Kansas, I was having none of it.

Who calls air-strikes on kids younger than themselves they don’t know, have never met, and who did nothing wrong—other than look different? Who deserves to be torched alive with fire jellies called napalm and chemically seared by burn agents like white phosphorus? Nothing any military professor taught at the university convinced me that waging war for no good reason was the way honorable people earned a living.

I wasn’t going to make a career out of killing people. I wasn’t going to spend five minutes destroying farms, livestock, and families to test the nation’s weapon-systems on human beings.

Read Being Hated to learn what my options were.

I made a decision certain to impact the future. Resigning my officer’s commission in the United States Army would shut doors; I had no idea at the time how many. Attending a music concert with new found friends who were unschooled in military discipline seemed like a good idea. My mother, working alongside the Navy pilot she married, bred and raised me for military life. It seemed that now might be the right time to learn another way.

At Goose Lake almost no one brought cameras. None in my group knew anyone except possibly their parents who owned movie cameras. In 1970, only rich folks owned color movie cameras with sound; still-pics were what ordinary parents took of their kids, mostly in black and white. Color cameras and film were expensive back in the day. Most movie-camera brands lacked sound.

It was a different time.

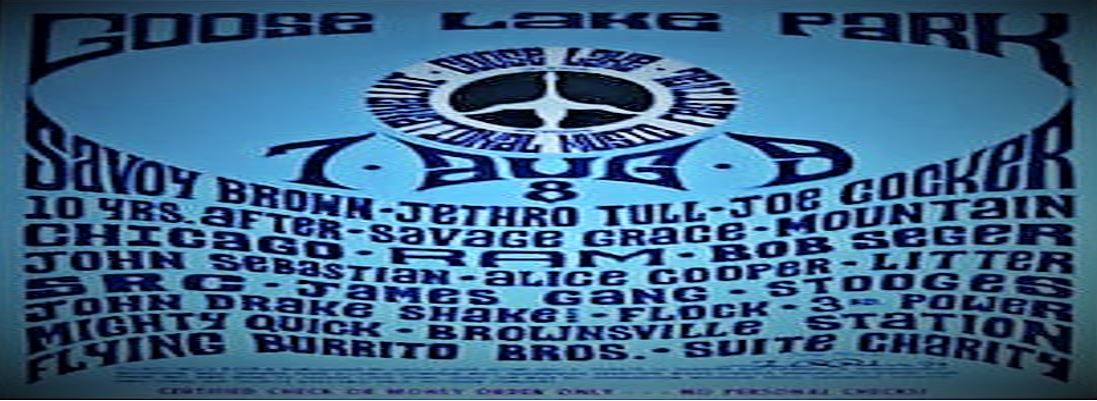

The photo and video records of the Goose Lake International Music Festival are almost non-existent as far as any web search done by me can tell. What video and pics remain are grainy, mostly black and white, and frankly depressing as hell, many of them.

No one showed up to produce a movie like they had at Woodstock in August 1969, the previous year. Woodstock, the Movie (edited by Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker) rolled into theaters across the USA in March 1970.

A whole lot of folks from Michigan decided to recreate the Woodstock Music Festival experience at Goose Lake. Within five months of Woodstock’s movie release, they managed to turn the fantasy viewed by most in theaters into a real-life, real-time spectacle for well over a quarter-million people.

Goose Lake was wild.

My new, radical friends brought to Goose Lake no change of clothes, no food, and no dope. They didn’t want to get busted by the pigs; everyone figured if we got hungry, food-stands would sell hot dogs to help get us through. We brought pocket change and pup-tents, nothing more. The way things went down, money (we called it “bread“) became the one thing we didn’t need.

We would require real bread—the kind people eat; readers will learn that some folks—like my group of friends—nearly starved at Goose Lake.

The concert turned out to be completely free once we worked our way inside. A fuzzy memory says we might have snuck in (like tens-of-thousands of others) through cuts in the barb-topped, chain-link fence erected to encircle the grounds and control the crowds.

I don’t remember anyone having money at the time to actually purchase $15 entry tokens, which have become collector items worth more now than then. ($15 in 1970 was equivalent to about $125 today.)

I remember the Goose Lake International Music Festival as a vivid technicolor freedom party.

In five days (we arrived early; stayed late), I learned more about anarchy—good and bad—than I learned during the following two years protesting the Vietnam war in the streets and the copy rooms of Joint Issue, the “underground” antiwar newspaper my closest friends published.

Goose Lake became for me the trip of a lifetime. This essay is an attempt to remember what I can before memories fade and go missing forever.

The first lesson learned was that people in America—white people who looked like me—used and were addicted, some of them, to heroin. I didn’t see anyone use heroin before Goose Lake.

Come to think of it, I don’t remember black people at Goose Lake, either. Through the lenses of today, the event might have seemed to the uninitiated like a gathering of white-supremacist men. Women attended, sure, but they made up not much more than a highly-desired minority—maybe 30%.

Heroin was what blacks ingested—that’s what white folks told themselves, anyway. It was the crack-cocaine of the 1960s and 70s. Whites didn’t do “hard” drugs—not according to news reports, which naive suburban kids who smoked weed suspected might mostly be sort of true but maybe not.

A black kid I worked with at Arlington National Cemetery trimming gravestones during summer confessed he tried it. He said heroin was so good he promised Jesus then and there he would never touch it again; he knew right away that if he shot it twice he would be toast—a lifelong addict with no hope of rescue this side of heaven.

What he shared was pretty much all I knew about a “hard” drug everybody heard of but no one used.

At Goose Lake we arrived early. My friends sat on a slope looking down onto a dirt parking lot. Cars, buses, and campers rolled-in like waves on a brown ocean. Dust hung in the air.

One car weaved; the driver seemed unable to negotiate a simple parking space. The car crawled almost to a stop when the driver-side door swung open; a guy in a white tee-shirt slow-motioned out the door—would he puke? As the car continued to inch forward, he plopped face down. Dust kicked up. His head hit hard.

The car rolled until it struck the back of a parked car. The door on the passenger-side jerked open. A girl leaned out; she fell like a sack of flour into the dirt.

The couple had finally made it to Goose Lake from wherever they came. Wrecked on heroin (or worse), they lay on the dusty lot for a while before dudes who wanted their blocked parking space got involved.

Maybe the couple ended up at the medical tent; maybe they recovered. I never learned what happened to them.

Things started moving faster; it was all anyone could do to keep up. As the festival revved—when security broke down, which as far as I could tell was before we got there, before the gates opened—pushers sold heroin in open markets to anyone who wanted to try; many did.

By the end of the festival, dealers were passing heroin free to anyone because they feared the gauntlet of police waiting outside the gates would arrest them on the way out. Festival goers heard that pigs were lined up at every exit and highway on-ramp to take revenge for being overwhelmed by the crowds.

When the time came for the festival to end, some people would be terrified to leave.

The folks who owned the food stands stupidly closed them the first night. Hungry people broke them down and took everything. By morning when my group went for breakfast, every concession stand was rubble. We wouldn’t eat again for three days.

As we stood around in shock wondering where to get food, semi-trucks rolled in loaded with tens-of-thousands of freezer-bags full of freshly harvested marijuana. Farmers from who knows where made Goose Lake a free pot zone. They tossed bags of grass from the back of their trailers for hours.

Someone brought papers. We rolled joints and stuffed them into empty cigarette packs—about 30 joints to a pack. For the rest of the festival we chain-smoked dope morning, noon, and nighty-nite-nite. Never before or since would I ingest as much THC.

Michigan grass is green and fresh; when lit, it smells like freedom. The farmers at Goose Lake brought their best weed and gave it away. I never understood why. Smoking weed was supposed to induce “the munchies.” I learned that you forget about hunger when you’re high enough.

At night I dreamed vivid dreams, not about sex, as was my habit during youth, but about baked potatoes piled high with butter and sour cream; steaks bleeding blood on the inside but burned black and crunchy on the outside coated with A1 sauce and spicy mustard; fresh cooked beans steamed in oil with lots of salt…

Dreaming about food made me feel joyful; glad to be alive. I knew I would eat these foods again and soon; I would ravage them with the appreciation deprivation provides. It is good to go without sometimes. It really is. Anyway, an unlimited stash of free dope lifted my spirits.

The music performed was uneven. Some groups came prepared to play; others, not so much. Music became a less interesting part of the festival, at least for me. A girlfriend who traveled with another group wandered around until she found me. She asked if I might try some mescaline someone gave her.

She said she wasn’t sure what it really was; it might be acid mixed with sedative; it might really be mescaline—an extract of peyote; all she knew for sure was that whoever gave her the pills promised it was mescaline.

I said, “Fine. Let’s drop some tabs an hour or so before the band Chicago performs. We’ll get off as the music starts.”

The night was going to be black and warm with a sky full of stars . My girlfriend promised to stop by my tent after the music started. She’d be high; we’d watch and listen together. I said, OK.

Night fell. I remember seeing light flash in streaks off gold trombones. Trumpets spit bursts of photons in all directions. The stage sat far away but was brightly lit. I saw sparkles of color flying off the edges of every item that shimmered.

I possessed the eye-sight of a predatory bird in flight. The music played crisp and clear. Percussive sounds splashed like warm rain across my face. I wanted to cry but amazement overwhelmed me.

My girlfriend showed up more or less on time and began to sway. I looked at her body, which I saw clearly through her dress with x-ray vision. My soul ached with desire. When I touched her she placed a hand on mine. Her dark eyes dilated—as I knew mine had. She leaned forward. “Want to?” she said. “I can’t believe how wet I am.”

We moved into the tent where she lifted her dress and wrapped her legs around me. I buried myself inside. We breathed heavy and made desperate sounds, which before mescaline we didn’t make.

Orgasm was intense. It took my entire existence. It lasted a lifetime inside a tent with its front flap open to the stars, music pouring in, and my newest friends nearby.

She, darling comrade whose name I’ve since forgot (God, forgive me), said something I won’t forget. “Billy!” she breathed. “I felt your orgasm—inside me. I felt it!”

Outside the tent, I stretched and yelled a grateful shout. One of the girls in my group poked her head out of the tent beside ours. “You shout after you ball? You are maximally stupid!”

The drug lasted. I wasn’t sure I would come down. Everything everyone said and did seemed to emerge somehow from an ocean of pearl-stones; miracles floated in the air like soap bubbles. I loved my mother—Gaia Earth—and everyone she carried with me, which included the girl in the next tent who called me stupid.

Without thinking or knowing what she had done, the other girl popped the biggest bubble of the most mystical moment of my life. It didn’t matter until decades later when memories were all I had left. Only then did my heart ache when I discovered I could no longer bring up the names of anyone I knew at Goose Lake. I forgot them all.

I saw bad things.

Iggy Pop of the Stooges performed after; he tried to bum the crowd by pivoting his play into a Pandora’s mess. While some started to flip-out and boo, I disassociated myself from the chaos. I witnessed bummer-terror sweep through the throng in the same way an entomologist might watch ants at war.

It was fascinating; entertaining, really. I floated like a prehistoric bird above the fray—superior to mortal sapiens who suffer in every way; I remained untouched by the vagaries of silly human cruelty.

A tall, thin kid got scared. He freaked-out. His acid trip went terribly wrong when he walked into a campfire where his ankles burned. I remember swarms of embers scattering like fireflies; he clawed the air howling like a wolf. A few folks managed to rescue and drag him flailing and kicking to the medics. He became a screaming madman. What happened later, I didn’t learn.

People built a mud pit, or something like it, near the stage. I heard folks say that a lot of people, mostly guys, were throwing themselves naked into the goo and wrestling in a huge pile. A girl in our group was there and ran back to tell us, “Guys are raping girls in that pit!”

No one believed her. No one went down to the stage area to check. The crowd was dense. You had to push and shove and step over people to get anywhere. Most folks like myself weren’t up for it.

The next day around noon, the Chief of Police walked into the crowd. He chose to wear coat-and-tie to conceal his identity. In that mass of half-naked, un-washed hippie-freaks, he stood out like a bulldog in a china shop.

A line of kids formed behind him. It grew to be hundreds as he made his rounds to inspect festival conditions and assess the level of lawlessness. The kids behaved like happy third-graders as they started chanting and singing. Some offered the bulldog dope. They thought they might “turn him on” to “our side”.

I think the Chief was surprised to get out of the park validated and unharmed. Had there been an incident, it’s hard to know now what his back-up plan might be. He had an army of thousands outside the park. Maybe undercover cops dressed like hippies watched his back.

Who knows?

After a few days, we started to starve. Someone noticed field corn growing across a nearby road outside the fence. It’s fed mostly to pigs but we thought, hey, we’re starving. It’s corn. How bad can it be?

Someone said, “The corn isn’t ours. We can’t take it.”

“Bullshit,” someone said. In minutes one of our own left to cut through the wire barricade; he returned carrying a few dozen ears, which we threw—husks and all—on the coals of our campfire. With mouths watering like sprinklers, we were able to remember to retrieve the corn before it burned.

We shucked and ate. It’s true what people say. Anything edible tastes good when you’re starving. I thought at the time that it was the best tasting corn of my life. To think that farmers fed it to pigs! The world starves, but American pigs eat like royalty.

I haven’t eaten field corn since.

On the last day a farmer drove into the campgrounds with a semi-trailer stuffed with raw potatoes. Soon, our group had all the potatoes we could carry.

It was the first time I ate raw potatoes. We had run out of wood for the fire. The potatoes were free like everything else but unwashed. We brushed off the dirt. They tasted great.

When we decided to leave, the crowds had thinned. We fully expected to be arrested. We got rid of our dope, which was worth hundreds-of-dollars outside the festival. Today it would be thousands-of-dollars.

We left it behind for the cops. I wonder what they did with it. Concert goers left behind an enormous stash worth, I don’t know, maybe millions. No one will ever know. Anyone who knew told no one as far as I’m aware.

We left without incident. The cops disappeared; they let us leave. They arrested nearly 200 people we learned later. I didn’t see any of it.

When I got home and the drugs wore off, I got scared. My stomach caught fire; I thought I was losing my mind. I couldn’t shake the fear. It occurred to me that I was going to have to kill myself.

I went to an emergency room doctor I knew who gave me a week’s supply of valium. I took it for three days. When I stopped, I felt fine.

My biggest regret is that I didn’t visit the lake. It was there, somewhere, but I never saw it or swam in it. The crowds were huge. A trip to the Goose Lake beach wasn’t worth the hassle, my friends decided. If we went and left our stuff, someone might cop our dope. It was better to groove by our tents and dig the music whenever musicians decided to play.

Is there a better way to end an essay than to provide readers with a pleasant, commemorative link? Click below to view a Facebook video from another perspective.

Remembering the Goose Lake Music Festival by Magic Bus

Billy Lee