Since Einstein said that E=mc2 , why does a massless photon have energy?

Someone asked a similar question on Quora. My answer garnered nearly a million views and many dozens of comments. It gave me an opportunity to gather thoughts on a subject that has puzzled folks for decades.

Of course, I’m a pontificator, not a scientist. I got advice from working physicists and incorporated what they taught me.

One thing I learned from science writer Jim Baggott is that Einstein first published his famous equation in this form:

M = ![]()

When written this way, it becomes clear that anyone who knows the total energy of anything can calculate in principle its total mass.

Einstein knew nothing at all about the Higgs field but today physicists agree that the mass it creates is less than 5% of what mass they have discovered.

In fact, nearly 99% of the mass of a single proton is derived from the energy of “massless” gluons that constrain its two up-quarks and one down-quark. Gluons are bosons which don’t interact with the Higgs field; quarks, which are fermions, do.

In the end, it’s all about energy, which it turns out is equivalent to mass, which according to Baggott is what quantum fields do. Quantum fields like the Higgs field make mass. Perhaps the electromagnetic field — which makes photons — does the same.

Here is Einstein’s equation for energy:

![]()

Since

![]()

and

![]()

it follows that it might be reasonable to imagine that photons have both internal mass and inertial mass, which causes Einstein’s equation for energy to give the following result:

![]()

All that is left is to divide by c2 to get mass, right?

![]()

Most folks think the internal mass of a photon is zero. Period. End of story. They use the two mass and momentum terms in Einstein’s equation to calculate total energy of massive objects, yes, but photons, they insist, lack internal mass. They lack the internal fermionic structures associated with all massive particles.

Photons do have inertial energy proportional to their critical frequency though, which suggests that they possess perhaps equivalent inertial mass, which drives the photoelectric effect.

When physicists take the energy measure of photons, they drop the mass term in Einstein’s equation. They set mass to zero and cancel out the first term, mc2. It leaves the second term — pc — which for photons simplifies to hf, inertial energy correlated to frequency, right? Energy can be measured in eVs, electron-volts, which are also units of mass.

If photons have internal energy, their total energy in the universe is undervalued by 1.414 (the square root of 2). Accounting for this added mass reduces the Cosmic energy deficit to near zero.

I should add that overestimating mass and disrupting popular models of the Cosmos is something most scientists think is a bad idea.

The gluon is the only other massless particle currently in the standard model, but it has never been observed as a free particle. All gluons are buried inside hadrons. It is their binding energy in quarks that makes as much as 99% of the measured mass of protons and neutrons.

So, there is precedent to possibly reevaluate mass equivalence of photons.

Some readers might wonder about the massless graviton. This particle is theorized to exist, yes, but has not been observed or added to the Standard Model. The same is true for dark matter and dark energy — no physical evidence; not added to the Model.

It doesn’t mean dark energy and matter don’t exist. Cosmologists see way too much gravity everywhere they look. The problem is they can’t explain exactly what is causing it.

As for my answer to the original question published on Quora, it was as accurate as my limited experience could make at the time, but the subject is controversial and several issues are not yet settled, even by experts. Some disputes might never be settled.

Who knows?

Not me. I’m a pontificator, right?

What follows is a version of the answer:

You might be mistaken about energy.

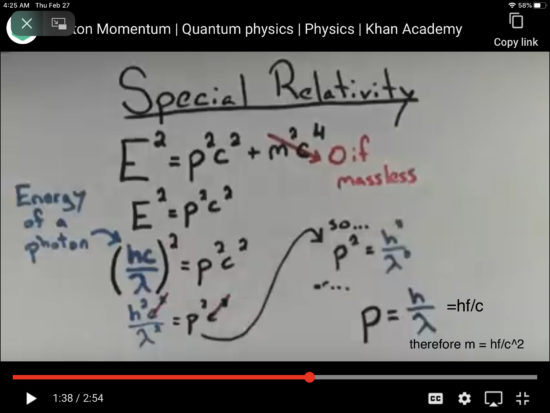

According to the complete statement of Einstein’s most well-known equation, energy content is a combination of a particle’s mass and its momentum. The equation you cite is abbreviated. It is a simplified version that is missing a term.

Here is a more complete version of Einstein’s equation:

![]()

—where m is internal mass and ρ is momentum. Internal mass is often referred to as “rest mass” because it is invariant in all reference frames and unchanged by velocity or acceleration. Momentum is inertial energy measured in equivalent mass units called electron volts (eVs).

Massless particles like photons have momentum that is correlated to their wavelengths (or frequencies). It’s their frequencies that give massless particles like photons their energy content. So without (rest) internal mass the equation becomes:

E=ρc

—where ![]() for massless photons.

for massless photons.

So, E = hf

[“h” is Planck’s constant. “f” is frequency. “c” is light speed.]

Of course, in classical Newtonian physics ρ = mc. The mass term is critical.

On the other hand, in quantum mechanics the total mass of photons cannot be zero either—photon internal mass is set equal to zero and eliminated. Inertial energy based on the photon’s critical frequency (the 2nd term in Einstein’s equation) becomes its equivalent mass. I’m not sure everyone agrees.

The beauty created by setting photon rest-mass (internal energy) to zero is it transforms the maths of relativity and quantum mechanics into structures that seem to be consistent and complete — able, one hopes, to meld into theories of everything; TOEs, if you like. The problem, of course, is that the convention of setting to zero leaves thrashing in its wake 95% of the mass and energy which “other” stories claim is hidden unseen “out there” within and around galaxies to move them faster than they ought.

The Abraham-Minkowski controversy seems to touch the argument. Click the link and scroll to the end of the article to learn how many things are disputed, not known, or unexplained. The science is not settled, although several physicists claim that the controversy is resolved by postulating an interaction inside dielectrics (like glass) of photons with electron-generated polaritons.

NOTE BY EDITORS: On 18 April 2021 a writer massively abbreviated and modified the article in Wikipedia on the A-M controversy. The writer deleted the entire list of disputed claims. Please click the link in this sentence to review a list of unsolved problems in modern physics. Photon mass inside dielectrics isn’t on the list.

The permittivity of “empty“ space (called the electric constant) qualifies as a dielectric, does it not? Isn’t space itself—with its Maxwell-assigned permeability (the magnetic constant) and permittivity (electric constant)—a dielectric?

Arthur Eddington wrote in chapter 6 of his book Space Time and Gravitation (read pages 107-109) that the dielectrics of space around the Sun increase proportionally with the intensity of the gravitational field. Light waves closest to the sun slow down more, which pulls the wavefront that lies farther out to deflect still more to catch up. Like glass, gravity refracts light.

Light falls into the Sun like any solid rock, but refraction adds to light’s “Newtonian” deflection to give Einstein’s predicted result. Unlike slow rocks, light travels fast enough to avoid capture by the sun.

It’s not clear to me how many physicists agree with Eddington, but then again, it’s not obvious whether humanoids are able to visualize reality. It’s one thing to write equations and symbolic algorithms that match well with observations. It’s quite another to acquire a natural intuition for what might be true.

Empty space isn’t empty, right?

As for the Abraham-Minkowski dispute: how important might it be to decisively resolve ambiguities concerning photon mass?

Perhaps the dispute is swept under a rug because disagreements about something as fundamental as photon mass mean that physicists might know less than they let on. The controversy seems to me at least to have the potential to crash the tidy physics of light and mass built by hard work and much history.

Isn’t it better to pretend everything is just fine until physicists finally agree that everything really is?

Maybe the subject involves some aspect of national security which requires obfuscation. It wouldn’t be the first time.

What I think can be safely said is that momentum and mass of quantum objects seem to have no meaning until they are brought into existence by measurements. The math looks like nothing we know; sometimes physicists use the results as mathematical operators that don’t commute the way some might think they should.

PHOTONS AND GRAVITY

I reviewed the math. I saw the term that makes the deflection difference (it’s really there) but did not understand enough at the time to tease out a satisfying reason why photons seem to bend nearly twice more in a gravitational field than early acolytes of Newton conjectured. I guess I like Eddington’s explanation best.

According to Wikipedia, Einstein’s theory approximates the deflection to be:

![]()

“b” is the distance of a photon’s closest approach to a gravitational object like our Sun.

Here’s some guesses I made before reading Eddington:

Maybe light deeply buried in a gravity field near a star like the Sun will experience the flow of time more slowly—it’s an effect common to all objects in a gravity field; it affects all objects the same way and is unaffected by their mass or lack of it.

It might have something to do with Schwarzchild geodesics. The geodesics of spacetime paths are longer and more curved in a gravity field than what anyone might expect from a simple application of Newton’s force law, which is oblivious to the spacetime metrics of Einstein.

Schwarzchild metrics help to explain the “gravitational lensing” of faraway objects when their light approaches Earth from behind massive gravitational structures in the far reaches of space. Light careens around the structures so that astronomers can see what would otherwise remain forever hidden from them.

Here is another guess:

It might be that light spends more time in a gravitational field than it should due to special-relativity-induced time dilations so that photons have more time to fall toward the star than they otherwise would. This guess is certainly wrong because the time differential would be governed by a Lorentz transformation.

Photons of light don’t undergo Lorentz transformations because, unlike massive objects that travel near the speed of light, they don’t have inertial frames of reference. Any line of reasoning that ties Lorentz transformations to photons leads folks into rabbit holes that contradict the current consensus about the nature of light. Light speed is a constant in all reference frames. Space and time expand and shrink to accommodate it.

Electron-like muons (which have rest masses 205 times that of electrons) are short-lived, but their relativistic speeds increase their lifetimes so that some of those that get their start in the upper atmosphere are able to reach Earth’s surface where they can be observed. Their increased lifespan is described by a Lorentz transformation. It’s tempting to apply this transform to photons, but theorists say, no. It doesn’t work that way.

Time contractions and dilations are Special Relativity effects that apply to objects with inertial mass that move in some specified reference frame at velocities less than the speed of light, yes, but never at the speed of light, right?

Nearly every physicist will insist that photons have no internal mass; they travel in vacuum at exactly the speed of light—from the point of view of all observers in every reference frame. Photons don’t have inertial reference frames in the same way as muons or electrons.

Changes in time and position caused by a photon’s location in a gravity field are completely different; they are described by a vastly more complicated theory of Einstein’s called General Relativity.

Here is one way to write his formula:

The terms in this expression are tensors, most of them. Click the link, anyone who doesn’t think tensors are difficult to write and manipulate.

Here is another way to think about photon energy and behavior:

Light follows the geodesics of spacetime near a massive object—like the sun. Gravity is the geodesic.

The difference for massive objects traveling at relativistic speeds is that their momentum and inertia enable them to skip off the geodesic tracks, so to speak.

Because massive objects always travel at speeds less than light, their “clocks” slow down through an additional dynamic (a Lorentz transformation) that works at cross-purposes to gravity. Massive objects lock onto the gravity geodesics for a shorter period of time. They undergo less gravitational time dilation than does light because they spend less time constrained on its geodesics. They jump the geodesic tracks to become constrained by the dynamics of the Lorentz transformations.

The result is that massive objects traveling at relativistic velocities less than light deflect less toward the star (Sun) than does light.

What makes General Relativity unique is it’s view that gravity and acceleration are equivalent. Acceleration is a change in the velocity and/or the direction of motion. Massive bodies such as stars curve and elongate the pathways that shape the space and time around them.

Photons traveling on these longer spacetime paths accelerate by their change in direction, but their velocity doesn’t change in any reference frame. Something has to give. What gives, what changes is the expected value of deflection. The light from distant stars bends more than it should.

SOME HISTORY

No one who lived before 1900 could know that the geodesics of space-time elongate (or curve) in the presence of mass and energy, which are equivalent, correct? No one in bygone eras could have known that time slows down for massive objects that approach light-speed, either.

A man named Joann Georg Soldner did a calculation to show how much a Newtonian “corpuscle” of light would bend in the Sun’s gravity, which he published in 1804. He assumed that photons had mass and fell toward the Sun like any other object.

When Arthur Eddington’s observations showed that starlight deflected more than Soldner had calculated, Einstein’s theories of relativity got a boost in credibility that lives on into modern times.

I should add that Eddington knew about Einstein’s predictions when he made his experimental observations in 1919 because Einstein had already published his general theory.

EXPLANATIONS

I would very much like to read a coherent, verbal (non-mathematical) explanation of exactly why and how Einstein’s general theory can lead to an accurate and reasonable prediction at odds with Newton about the angle of deflection of photons near a star.

Here is a synopsis of an explanation that I heard from a working physicist:

Soldner used Newton’s view to calculate deflection using only the time the photon spent in the gravitational field. Einstein did the same but then modified his calculation to account for the bending of space in the gravitational field. The space component nearly doubled the expected deflection.

The theorist’s explanation satisfied me. It sounded right.

On the other hand, I believe (secretly and in agreement with Newton’s acolytes) that photons must have a mass equivalence that for some reason is being discounted, but no one I’ve read believes the idea makes sense beneath the shadow of a relativity theory that has the reputation for being fundamental, flawless, and complete.

After all, the mass of any object in a gravitational field is irrelevant to its trajectory because the mathematics cancels it, right?

![]()

Little “m” appears on both sides of the equation so it can be divided away.

The problem is that the equations for gravity—especially over cosmological distances—are not necessarily settled. These are serious anomalies that are not yet resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. Some have direct consequences on the ability of organizations like NASA to conduct accurate landings on Mars and the Moon. Click the link in this paragraph to review six of the biggest puzzles followed by seventeen alternative theories designed to bring the discrepancies to account.

Anyway, mass-energy equivalence of photons might permit Lorentz transforms on light to help to resolve certain problems in cosmology and the transmission of light through medias where gravity is not a factor. It might also simplify understanding of annoying Shapiro effects, which slow down communications with explorer craft inside our solar system.

ANOTHER EXPLANATION

Since I haven’t yet found a good explanation—and with a promise to avoid nonsensical personal predispositions—here is my attempt to explain:

In GPS (Global Positioning Systems), dilations of time—in both the velocity of satellites in one frame and their acceleration in another frame (gravity)—must add to provide accurate information to vehicles located in another frame.

These time dilations can work at cross-purposes. It requires expensive infrastructure on the ground to coordinate the information so that drivers of vehicles don’t get lost.

A massless object moving at the speed of light is going to follow the geodesics of the gravity field. This field is a distortion of space and time induced by the presence of the mass of something big like the Sun.

If massless energy does not obey the laws of Special Relativity (like GPS satellites do), then its velocity must necessarily have no influence whatever in the deflection of light near a star. It might seem like all the deflection comes from the distortion of spacetime, which is gravity.

Photons ride gravity geodesics like cars on a roller coaster. According to appendix III in Einstein’s 3rd edition of his book, Relativity, the Special and General Theory—published in English by Henry Holt & Company in 1921—it’s only half the story.

The other half of the measured deflection comes from the Newtonian gravitational “field”, which accelerates all objects in the same way. This field further deflects light across the spacetime geodesics toward the sun to double the expected angle.

I’m not entirely convinced that modern 21st century physicists believe it’s quite that way or quite that simple.

CONCLUSION

The theory of general relativity helps theorists to describe the distortion of metrics in spacetime near massive bodies to predict the deflection angle of passing photons of light. What we know is that predictions based on the theory don’t fail.

It’s like the theory of quantum mechanics. It never fails. It’s foundational. No one has yet been able to explain why.

Somebody, please, tell me I’m wrong.

Here is a link that addresses the math concerning the deflection disparity between Newton and Einstein.

Billy Lee

Readers interested in this subject will learn things from the material in these comments, I promise.

Billy Lee